field notes: masterclass on trauma-informed practice

A little more than a week ago, I attended a Trauma-Informed Practice Masterclass, as part of the NUS SSR-Touch Conference 2025 and it sent me on a rabbit hole thinking about care.

As part of the masterclass, Ms. Yogeswari Munisamy, passionately share about her PHd research on a trauma-informed practice - recognising that trauma does not only exist in clients but echoes within the system and professionals who hold space for them - affirming the senses I’ve gathered ever since my practice intersected with the social service sector 8 years ago. In line with this year’s conference theme on Sustained Well-being in Future Ready Communities, I left the conference wondering about the ecosystem of care in our world today, even beyond that of the social service sector.

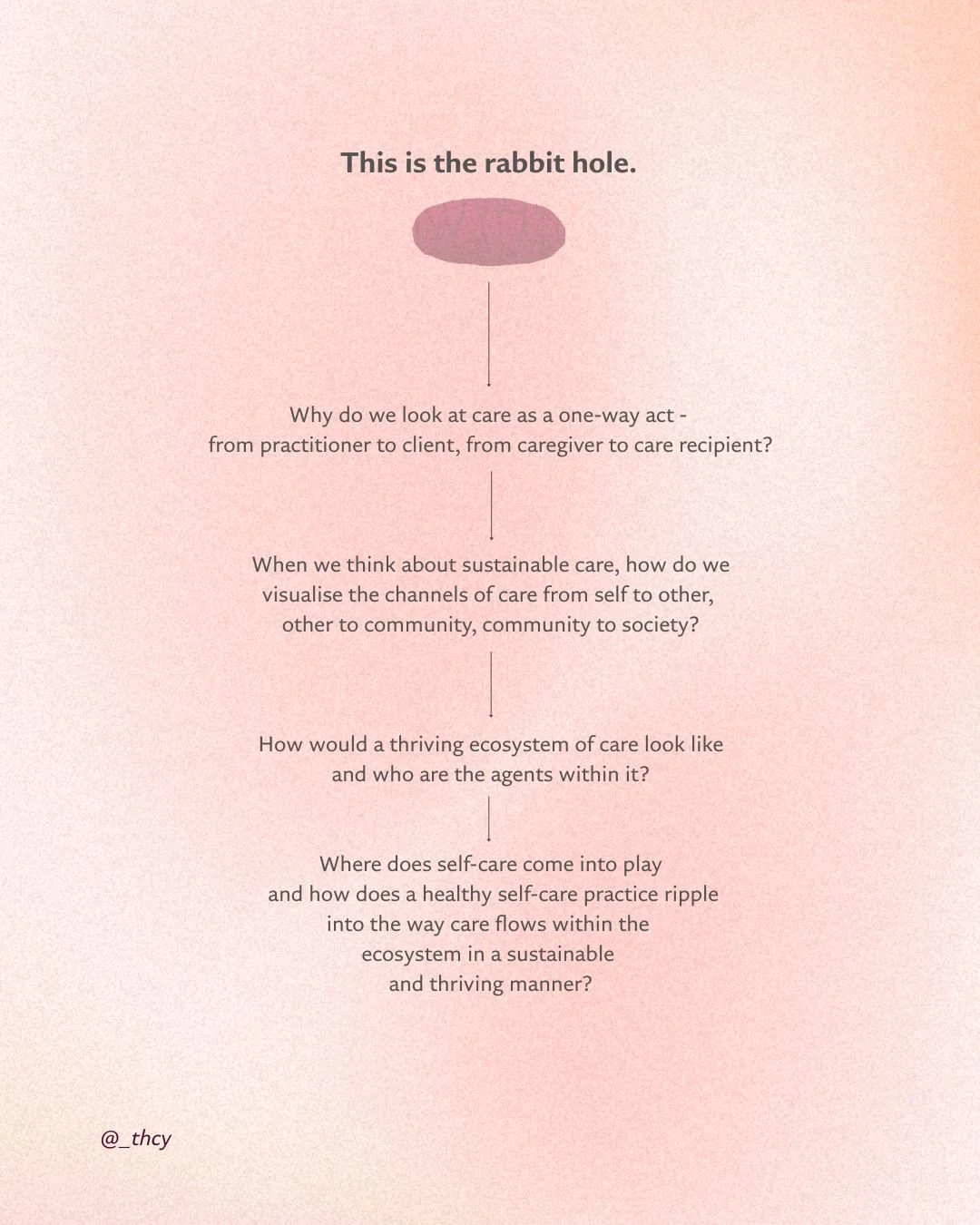

A rabbit hole of questions in relation to care.

As I got to learn more about trauma-informed care, it brought to the surface an awareness. While all of us, in one way or other, already carry trauma with us, practitioners take on an additional load in the form of secondary trauma. As part of their day-to-day practice, they bear this extra weight while having to meet clients, hold space for them AND are expected to carry out their regular admin duties in order to basically help to save the world. Over time, a work life of a practitioner becomes one where energy and emotional labour is poured out more than it is replenished, leading to compassion fatigue and stress, amongst many other long term repercussions.

My takeaway from hearing about the research is that care has to be part of the picture much earlier and for all the players in the care ecosystem as part of our day-to-day rhythm, not just for the ones in the frontline or after trigger and exposure to secondary trauma. Care in the form of spaces that don’t just seek to ‘fix’ or ‘help’ but to witness - to hold without absorbing, to listen without losing oneself.

Introducing tend, an evolving reflective model inspired by gardens and seasons, where I integrate embodied reflection and creative tools into the coaching framework to tend to our inner landscapes as a form of care. In this model I have been developing, paying attention sits at its core where like trauma-informed care, the act of tending holds attention in two directions: one toward the other, one toward your self. Especially so for caregivers, care workers and practitioners, this dual-attention is important not just as a practice of noticing but also in helping to reinforce our boundaries and ensuring emotional and psychological safety. In paying close attention to ourselves, we are better able to notice when our boundaries are crossed, when our energy is getting depleted and when our capacity is being reached. Then and only then, are we able to step in and take the necessary acts of care for ourselves.

tend’s model recognises that the reality of the day-to-day makes this easier said than done. Hence, tend is designed to offer that space for one to notice and give attention to what will otherwise be neglected or deprioritised. By tending to ourselves like gardens, it is about embodying the philosophy that our lives are made of varied seasons and that the processes of planting, rooting, rest and harvest has its own place and time. When applied to care, it helps us to see as a garden that is constantly being harvested for its attention, it will eventually deplete itself, leaving nothing for the garden to recuperate, grow and much less, flourish.

For a garden to be self-sustaining and also contribute to a larger ecosystem of gardens, it needs to be tended to.

The process of tending helps us to take stock of our garden - to be aware of what has taken root, what needs pruning and what is slowly withering away. It also helps us notice what is thriving and growing and what is ready to be harvested when we are called to provide.

If there is one thing the masterclass affirmed, it is this: the well-being of our care ecosystem depends on how well we tend to ourselves. Care is much less a skill, than it is a practice that moves with the season. We need spaces where practitioners, caregivers and community workers can come home to themselves, even briefly and it has to be woven into the everyday rhythms of those who give, serve, guide and support. In shaping tend as a reflective practice, it is not to teach practitioners to care more, but to care differently . My hope is that tend becomes a space for practitioners to pause, notice, replenish and return - to not just recover but to also cultivate new capacity and ways of being with each other.

If we want our systems to hold people well, we must first learn to hold ourselves, and that begins with noticing what needs tending.